The first time that I was asked to make a toolbar for Firefox my first thought was, "sounds like fun!" However, I didn’t have a clue about where to start and how to find the information about it. I wrote this post to share my experience and help anybody who finds himself in a similar situation

Toolset

For this tutorial is recommended that you have the following software installed:

Firefox 3.6 or later

Extension Developer (ADD-ONS for Firefox)

Visual Studio 2008 or 2010

Text Editor

How to Create a Toolbar with XUL

To create a toolbar we will use the following,

- toolbox: A box that contains toolbars.

- toolbar: A single toolbar that contains toolbar items such as buttons.

- toolbarbutton: A button on a toolbar, which has all the same features of a regular button but is usually drawn differently.

- toolbarseparator: Creates a separator between groups of toolbar items.

- toolbarspring: A flexible space between toolbar items.

- menu: Despite the name, this is actually only the title of the menu on the menubar/toolbar. This element can be placed on a menubar/toolbar or can be placed separately.

- menupopup: The popup box that appears when you click on the menu title. This box contains the list of menu commands.

- menuitem: An individual command on a menu. This would be placed in a menupopup.

- menuseparator: A separator bar on a menu. This would be placed in a menupopup.

To start, do the following,

Open Firefox

Open Real-time XUL Editor of Extension Developer or any page of XUL Edit online like (e.g., http://ted.mielczarek.org/code/mozilla/xuledit/index.html)

Copy the following source,

<?xml-stylesheet href="chrome://global/skin/" type="text/css"?>

<window id="yourwindow" xmlns="http://www.mozilla.org/keymaster/gatekeeper/there.is.only.xul" xmlns:html="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xmlns:h="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml">

<toolbox>

<toolbar>

<toolbarbutton tooltiptext="tooltiptext1" oncommand="functionJS_1()" label="LabelButton1"/>

<toolbarseparator/>

<toolbarbutton tooltiptext="tooltiptext2" oncommand="functionJS_2()" label="LabelButton2"/>

<toolbarbutton tooltiptext="tooltiptextN" oncommand="functionJS_N()" label="LabelButtonN"/>

<toolbarspring/>

<menu label="LabelMenu" tooltiptext="tooltiptextMenu">

<menupopup>

<menuitem label="LabelMenuitemCheckbox1" type="checkbox"/>

<menuitem label="LabelMenuitemCheckbox2" type="checkbox"/>

<menuitem label="LabelMenuitem" oncommand="functionMenuitem();"/>

</menupopup>

</menu>

<toolbarseparator/>

<menu label="Help" tooltiptext="About this toolbar">

<menupopup>

<menuitem label="Visit blog of nearsoft" oncommand="OpenNS();"/>

<menuseparator/>

<menuitem label="About this toolbar"/>

</menupopup>

</menu>

</toolbar>

</toolbox>

</window>

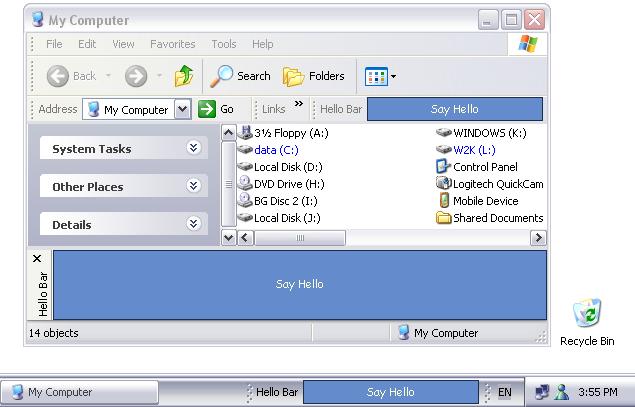

After you paste the source on the XUL Editor it will show you the preview, which will look like this,

Read more: closerisbetter